The air we breathe: indoor air quality and building maintenance

Indoor air quality (IAQ), often regarded as an opaque element in building management, has suddenly jumped to the top of the agenda for facilities managers and landlords following the coronavirus pandemic.

It is long overdue explains Gavin Phillips, environmental chemist and physicist at the Centre for Research into Environmental Science and Technology (CREST) at the University of Chester part funded by the European Regional Development Fund.

“Air is complicated. You can’t see it so, unfortunately, it often drops off the list of priorities for building managers. But we know quite a lot about the impact of poor air quality on areas such as productivity and concentration. Now we’re all trying to better understand how it transmits airborne viruses as well.”

Gavin is currently working alongside resero to translate the latest research knowledge on air quality into better building management.

COVID-19 and air quality in buildings

The role of indoor air-quality in coronavirus transmission is a particular area of uncertainty.

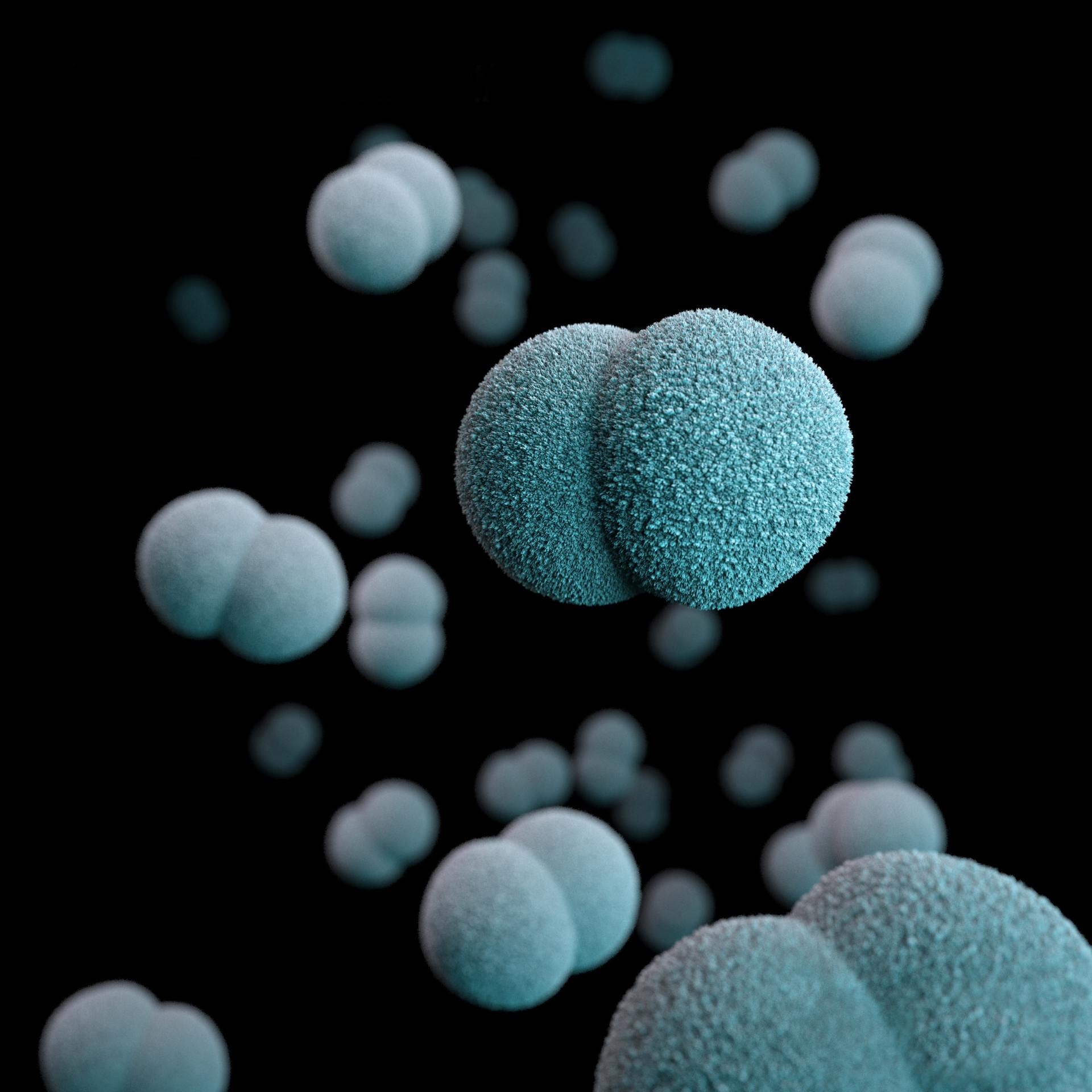

Current government and public health guidance is focused on large droplets emitted by coughing, sneezing, talking or breathing heavily. These droplets tend to quickly fall to the ground or on surfaces where they stay active for varying amounts of time, depending on the material of the surface.

However, alongside these larger droplets, tiny droplets and particles, called aerosols, are also emitted. These can stay in the air much longer and travel much further. Because they are smaller they also tend to be inhaled deep into the lungs.

More than 200 scientists worldwide have written a letter to the World Health Organisation (WHO) pointing to strong evidence that these smaller particles are playing a key role in transmission of the virus – particularly in crowded or closed-in areas with poor ventilation.

Improved air quality vs energy efficiency

“Virus transmission events seem to occur in badly ventilated indoor spaces. So, ensuring that mechanical and natural ventilation systems are working optimally is really important,” Gavin says.

Commercial buildings use air handling units (AHUs) equipped with filters designed to capture dust as well as pollen and bacteria particles. Some of these filters are also able to capture the smaller aerosols and trap them within the filter.

However, not all buildings will have these filters. Even those that do can often find the filters are not installed correctly or do not meet current British and International standards for particulate matter efficiency.

These filters also create an energy conundrum for building managers - the smaller the particles captured, the more energy required by the AHU to push the air through them.

Andrew Cooper, a director at resero, says energy efficiency and fixed maintenance regimes have dominated building operation and management, sometimes to the detriment of air-quality and occupant health and wellbeing.

For example, he says, it is by no means normal practice to install CO2 sensors in buildings. Where they have been installed, their primary purpose is to save energy.

“Operationally speaking, the sector has never really focused on what optimum air quality is and how you maintain it. Currently CO

2 levels are used as the sole proxy for fresh air, and any ‘optimisation’ of fresh air (where this is this even possible), tends to be reliant on automatically adjusted BMS settings.”

We don't know enough about air quality in each building

The issue is that while we now know a lot about air quality and its impact on productivity, concentration levels and health, we still know very little about the indoor air quality within an individual building. This includes:

- how to identify, control and maintain optimum IAQ

- how to effectively control the movement of air inside a building

- the relationship between IAQ and outdoor air quality (OAQ)

- the relationship between IAQ and occupant actions

- the relationship between operational actions to save energy and carbon emissions in a building and the impact on IAQ

This is why the current industry guidance on making offices COVID-19 safe has had to rely on blanket recommendations. The most influential of these, from the Federation of European Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Associations (REHVA) recommends:

- installing higher quality filters in air handling units (AHUs) capable of capturing aerosols in the return air

- avoiding recirculating air wherever possible, even where there are return air filters in place (unless these are medical grade/HEPA filters)

- ensuring air handling units (AHUs) and fans are operating 24 hours a day to ensure maximum levels of fresh air and that air is moving constantly.

However, adopting the REHVA recommendations on every building will, Andrew says, cause a huge spike in energy consumption and carbon emissions. It will have a massive impact on efforts to achieve net-zero earlier than 2050 – an equally urgent problem.

“We have to find strategies that can maintain optimum air quality and velocity, minimise transmission rates and reduce carbon emissions all at the same time. The answer is we need to switch to more responsive buildings. For example, AHU filters are usually changed on a fixed basis or when things have gone wrong or failed. There’s currently no link between this maintenance regime and any monitoring of air-quality or filter effectiveness.”

He says most building managers and even engineers do not even have a note on whether filters are side withdrawal or front withdrawal and/or if they are correctly sealed to prevent unfiltered air bypassing the filter – a particular problem for side withdrawal filters.

Research project

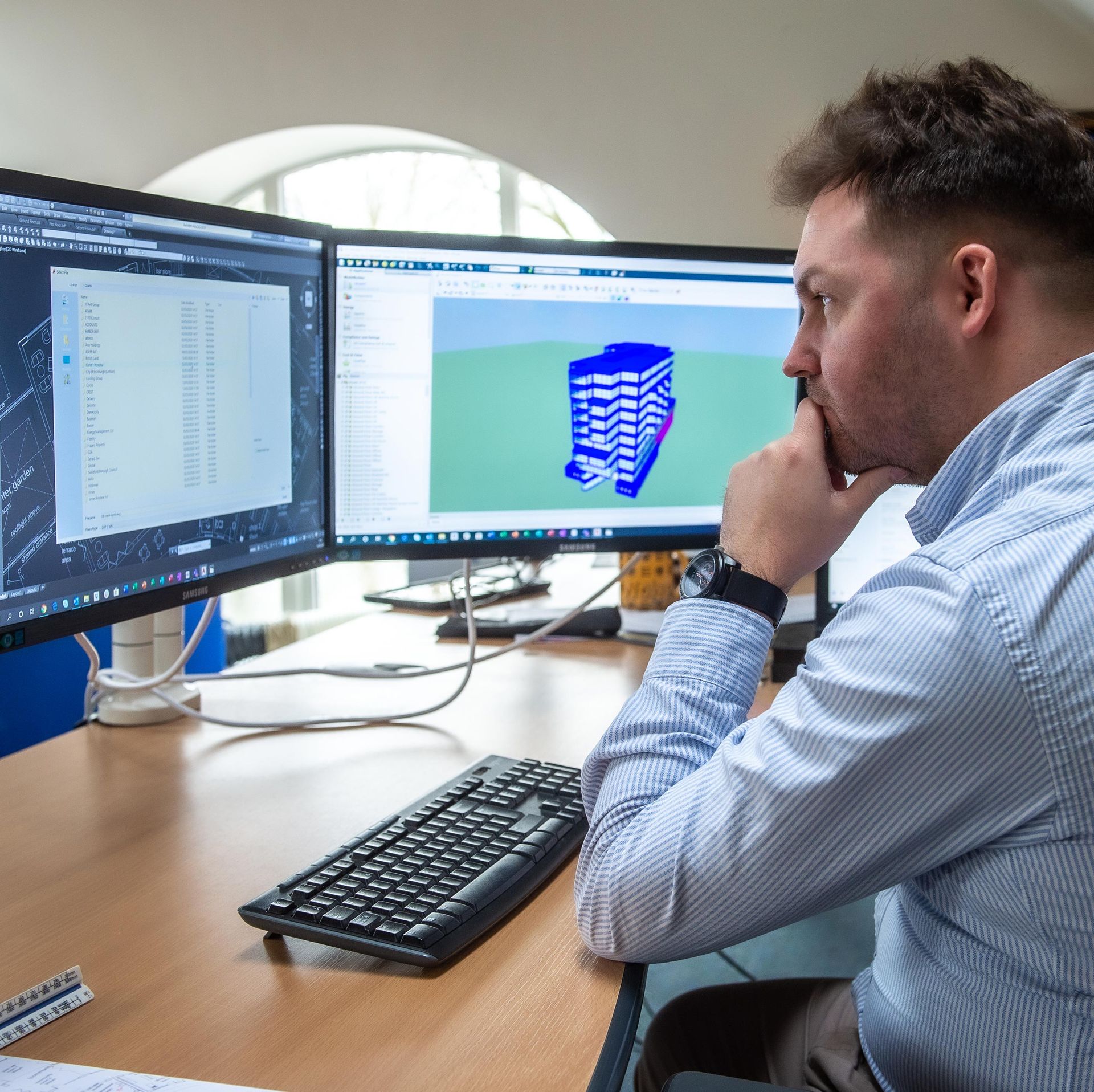

The joint CREST and resero project will use detailed sensor monitoring and data to look at the impact on IAQ of changes to the building operation and maintenance that are put in place to reduce energy and carbon emissions.

The detailed sensor information could also be provided to occupants via a user friendly website or app. This would provide greater transparency and choice over their return to work following the virus lockdown.

Andrew adds: “Occupants could decide to work from home, use a different meeting room, go for a walk or even just open a window if they can. This may help provide confidence in the work environment, something that will be required if we are to get back to ‘normal’ operations.

“Our long-term goal is to incorporate IAQ into software that would not only ‘instruct’ an automated building management system (BMS) to make immediate changes to improve air-quality but also embed IAQ into contractor performance through our auditing tool. For the first time IAQ and energy efficiency will be part of the fabric of how a building is operated and maintained."

As Gavin points out: “The one really powerful tool we have in this area is our control over the building. At the moment that impact is often by accident, but if we can be more purposeful we could make a real difference.”

Gavin and resero will initially be working with the Wrekin Housing Trust, one of the largest providers of social housing in the West Midlands and Aberdeen Standard Investments as part of the research.

If you’d like to take part in the research then please contact info@resero.co.uk or call +44 (0)1743 341903. If you’d like to be kept up-to-date with the findings of the research project please

sign up to our monthly newsletter.